- Home

- Samuel Archibald

Arvida Page 4

Arvida Read online

Page 4

“Lynxes?”

“A lot bigger than a lynx. I’m talking about something about as big as a tiger, that could jump from over there to this tree here without even having to take a run at it. An animal that would make a meal of just about anything. From a rabbit to a moose.”

“So there’s a big cat in the hills?”

“Like I said doctor, you don’t have to believe me. I can only tell you what I know. There’s been no big cat killed around here for a hundred years, but I know some fellows who are in the woods all the time like me, who say it’s still there.”

The doctor was thoughtful for a moment. Jim’s father took the opportunity to add:

“If it turns out that your dog disturbed this cat while he was on a scent. You can’t know what one, that of an animal maybe, but maybe yours, or my son’s.”

“If that’s what happened,” said Jacques, continuing the train of thought, “then maybe Spencer saved Jim’s life.”

The doctor decided to bury Spencer right away behind the trailer. He brought out some scotch that the three men guzzled from the bottle while digging the hole, and he gave Jim a Saguenay Dry. By the time they headed back it was dark and they were drunk and it was Jim who lit the way with his flashlight. When his father and Jacques had gone a good distance from the trailer, his father said:

“That was some lie.”

In the trappers’ cabin, a bit later, Jim went up to Jacques and asked:

“Trapper, did it ever exist, that creature you were talking about before?”

“What creature?”

“The big cat.”

The trapper pointed to the shelf about two feet from the ground running around the cabin’s four walls. On that shelf there were the whitened skulls of dozens of animals, in decreasing size. It began with two big bear heads and five wolf heads, going down to the many tiny heads of martens and mink, of groundhogs and squirrels. Between them there were the heads of coyotes, of lynx, of foxes, of fishers, of porcupines, and even a wolverine. All that was missing was a moose, but a large set of antlers was attached to a horizontal beam and rose up over their heads, casting frightening shadows onto the ceiling.

“I’m going to tell you something, Jim. If it’s not on the shelf, it doesn’t exist.”

“Yes, but Jacques, there’s no human head on the shelf, and they exist.”

The old man smiled and brought his old hands down, like an eagle’s talons, onto his head.

“If you’re going to be a smarty pants, yours’ll be up there next.”

The doctor decided to move, and to set up his trailer a little less deep into the Controlled Harvesting Zone, where all the species were tracked. Still, he came to see us two or three times over the following weeks and he’d made his own inquiries. There really had been, he said, a big cat in the mountains. A ferocious animal, two metres in length, and capable of mighty leaps. Perhaps it was still there, yes, it was entirely possible, and that would explain everything. Doctor Duguay liked to sprinkle his sentences with Latin phrases, and from his grand pronouncements Jim had retained one term that echoed in his head ever after.

Felis concolor couguar.

*

Late January.

The men are gathered around the broken trap, far enough away not to interfere with the prints in the snow that start in a small coniferous wood on the other side of the small valley where they’ve left their skidoos, cross the snow-covered land, sweep around the shattered cage, and plunge even deeper into the bush. Jim had been able to follow them for thirty or so metres before losing them for good between two big balsams, whose warmth had made soft holes in the snow.

“You say that nobody’s seen that bugger since the 1940s?” asks Bernard.

“1938,” says Jim. “They killed it at the Maine border.”

“And they’ve come back?”

“Maybe they never left. Hard to know.”

Bernard looks at Jacques Plante the trapper.

“And you believe that?”

“It’s not a matter of believing or not believing. There are some biologists from the University of Montreal who put out some bait. About fifty miles that way. They must know what they’re doing.”

Jacques Plante the trapper, on his snowshoes, bends over the two paw prints, big as saucers. Between the prints there are lines you’d say were whipped into the snow with sticks. Jacques clears his throat, sends a large gob of spit flying forwards, and looks in turn at Bernard, his brother-in-law Roland, and Jim.

“That sure looks like your cat. To make lines like that in the snow, you need a big tail.”

Doris, sitting against a birch trunk a few steps behind them, says:

“It could have been a wolf.”

“Yeah, but they don’t hang out around here this time of the year. And that’s not a wolf I saw.”

Very early that year, November burst winter wide open to let in the wind from the northwest, and a little dry cold that bit into your cheeks and chilled your blood. Everyone is dressed in thick fur jackets or parkas. Doris and Jim are also wearing scarves over their lined hoods, to protect their faces. The sun is an opalescent smudge in a white sky that glints on the dark glasses of Bernard and his brother-in-law. The trapper asks:

“Find any hairs?”

“Nope.”

“And the pictures, Jim?”

“The pictures? Not great.”

Jim’s holding a digital camera in his hands that’s very practical because you don’t need film and you can see your photos on it right away. But those machines don’t like it when it’s really cold. The screen keeps flashing the message, “Battery error.” Jim has to turn the camera off and heat it up in the inside pocket of his coat before turning it on again. Twice already he’s scrutinized the least blurry of the three shots Bernard took, on a screen not much larger than a postage stamp. He saw black lines and blotches in streaks on a white background, he recognized the leafless trees and the conifers pushing up from the thick layer of snow on the ground. Beyond, behind a scrawny spruce and the thick trunks of two birches, there was an indistinct patch of fairly dark beige. Peering at it, squinting his eyes before the sun and the gleam of the sun on the snow, he saw the muscled torso of an animal take shape, with two powerful legs and a tail thrust into the air like an apostrophe. He followed the shape frontwards until he saw the head almost totally hidden by a tree trunk, and then part of the face, the curving arch of an eyebrow, the erect tip of an ear, the muzzle with a black spot on its surface, and the vague silhouette of a small creature thrust into its mouth like a gag. The camera freezes again, and now Jim can no longer reconstitute the image with so many details. Every time he turns on the camera the picture seems softer, as if someone had wanted to take a photo through a window just to capture his own reflection in the glass.

Bernard’s skidoo had broken down earlier in the day, while he was making the round of his traps with Roland. As he had his snowshoes and he knew he was very near two traps, he sent his brother-in-law back to the camp for spare parts and tools. They were on a large expanse of level ground, and Bernard began to advance, hearing no sound but the crunching of his snowshoes in the snow, the buzz of the other departing skidoo, and from time to time the cry of a squirrel. After walking for ten minutes he entered the dark woods, and stopped short on hearing a loud commotion. He advanced slowly, making no noise. He saw a large beast tearing apart his trap to reach the animal trapped inside. He was never able to say if it was a marten or a mink, because the huge creature fled, bearing it off between its jaws. Bernard had time to take a few photos before it was out of sight. He was panting, his heart was pounding, and by the time he got back to the skidoo he was close to blacking out. He took his portable radio and called Jim’s father on their usual frequency, “I think I’ve just seen Jim’s cat,” he said.

Afterwards, he gave them his coordinates with the GPS. Jim

and his father dressed rapidly, and his father filled the skidoo’s gas tank while Jim called Jacques Plante the trapper and Doris on the radio.

Now they’re all there, studying a photo that reveals nothing, and tracks that will have largely disappeared by the next day, when the Wildlife Service agent arrives. Jim should be disappointed but he isn’t, not that much. He and his father take off on their skidoo and criss-cross through the underbrush until darkness falls, taking turns at the controls and peering as far as they can through the branches and trees. His father talks always of his cat in the singular, and Jim very much likes that. “You’ll see, we’ll find it,” he says. “One fine day it’ll pop out right in front of us.”

Of course, if there are still cougars around, it’s logical that there would be several, but Jim also likes to think of it as a lone animal, immortal, like the Yeti or the Loch Ness Monster, a creature that hides for the pleasure of being tracked, and shows itself from time to time to revive its own legend.

In these valleys where it sometimes snowed non-stop for days at a time, and where violent thaws and freezes succeeded each other with no sequence or logic, winter was more than a season, it was a landscape superimposed on another, where you had to orient yourself according to rare, unvarying signs in the snow and the intense cold.

Gaétan Fournier, a friend of Jim’s father, had his cabin in the bottom of a valley. There the accumulation of snow was so great that one year, at Christmas, Gaétan, his wife, his daughters and his sons-in-law, had to dig out the cabin with shovels from eleven o’clock in the morning until dusk. He’d stopped in the middle of nowhere on immaculate terrain, had got down from his skidoo and begun to take his snowshoes and round point shovel out of the sleigh. One of his sons-in-law had said:

“What are you doing, sir? Seems to me that the camp is still quite a ways.”

Gaétan had replied:

“The camp is under my feet.”

They’d shovelled as far as the cottage, lit a fire for the women with the wood they’d brought with them, and then shovelled some more until they’d reached the woodshed. They’d taken out logs and made a great inferno in the snow, slathering the wood with old motor oil. The next day their camp and its surroundings formed a huge crater in the snow-covered valley.

The snow built up on spruce and fir, gathered in thick layers that the deep cold hardened onto their branches. As of mid-December, whole hectares of the forest were transformed into dolmens of white ice that blazed under the boreal sun, as dangerous for the eyes as a welder’s flare. People came from the ends of the earth to meander through this lunar, monotone landscape.

When an outsider asked local people if they had a name for what they saw, they replied, “We call them ghosts.”

*

Early May.

Half asleep, he’s running on four legs, is conscious of the strength of his muscles in movement, and feels branches brushing against his fur. In great bounds he leaps the rushing water and dead trees that the forest throws up in his path. Half asleep, he hears his father, Doris, and Jacques Plante the trapper talking, seated around the table a few metres from his bed. He knows the beast is tracking something, he’s breathing a heady smell through his nostrils, sees through his dilated pupils the prey’s silhouette far in the distance, it stands out against the green of the trees, which he has never known so vivid. Half asleep, he swoops down on the prey and recognizes it. It is himself. The cougar is attacking him, and he is the subject of those fragments of conversation he’s hearing from the far end of his dream.

“How long had it been since he’d had the sickness?”

“Four years.”

There is silence. The beast buries its teeth in his throat and he tastes the salt warm blood that is loose in the creature’s mouth.

“That mustn’t have brought back good memories.”

“Not really, no.”

Two weeks earlier, Jim had come home alone from school, knowing that it had returned. It had been stalking him already for several days, like an evil shadow. He managed to open the door despite his trembling and the unruly beating of his heart.

His father, sitting at the counter, saw him come in, and leaped up.

“Jim, what’s wrong?”

He wanted to talk, he wanted to cry out, but by that point it was already in total possession of his body. He was elsewhere. For a long moment his father looked on as his son’s body was wracked by convulsions, arched back on the ground, the eyes rolled upwards, then he took him by the shoulders, turned him on his side, and began humming a lullaby while passing his hand over his sweat-dampened hair.

A few days after the crisis, he fell ill. The flu, which worsened over the period of a week. He wasn’t eating, and had a consumptive’s cough. His father took him to the doctor, who diagnosed a serious bronchitis and prescribed antibiotics and a great deal of rest. The next day, from his room in the city, Jim overheard his father talking on the ham radio he kept in the basement to communicate with people up north.

“He’s not doing that well, Doris.”

“Why don’t you bring him up to the woods?”

“I can’t, not before the weekend.”

“We’ll come and get him, then. Antibiotics are fine, but I’ve got two or three other things in mind.”

Now he’s in his bed at the cabin and it’s night. His father had arrived a bit earlier, had sat down on the covers beside him and placed his hand on his chest. Behind them, Jacques Plante the trapper was seated at the table in front of a beer, eating pieces of cucumber. Doris was busy at the stove.

“Feeling better, boy?”

“Yes, papa.”

“Yes, he’s better. He’s been eating well since this morning. But he sleeps, the little rascal. Now we’re going to make you a mustard plaster and you’re going to go beddy-bye. Same for you, old man, you’re going to have a bowl of soup and some tourtière and you’re going to bed. You look tired too.”

Doris stirred up two teaspoons of dry mustard in a bowl, along with cornstarch and cold water. She spread the plaster over an old cloth that she applied to Jim’s chest. It was hot and dizzying. After five minutes, she came to lift it off for a few seconds, and kissed him on the brow. After a half-hour, she took it away altogether.

Now Jim is dreaming and listening. He hears what they’re all saying about him. He’d like to reassure them, to explain to them. He often has a dream with no up nor down, where the beast attacks him and devours him. It’s a dream of carnivorousness and violence, but not of death. He does not expire while the cougar is annihilating his body, he fossilizes within the animal like a memory of flesh. In its belly he dreams himself into a child itself of dreams, the stillborn offspring of a legendary creature, and there’s colour in the dream, and the sounds dogs make, dozing next to the stove.

“Jim’s sleeping,” says Doris.

*

Jim often fell asleep just so, and listened in snatches to adults talking close by. He rolled over in his bed, and an hour was gone. He missed whole swathes of conversation. At one point he realized that his father was lying in bed in front of him, and only Doris and Jacques Plante the trapper were up and about. Like diligent angels, they watched over their sleep, and put the cabin in order while talking quietly.

They picked up full ashtrays and set them on the counter with a little water in them before emptying them into the trash. Jacques Plante doused the last cigarettes in a bottle of beer. In one of the two big dented kettles that Jim went to fill every morning and night at the lake, they put water to boil on the large burner of the Vernois stove, whose high flames licked the metal almost to the bottom of the handle. Jacques Plante emptied the boiling water into the dish tub in the sink, and the shadows filled with long wreathes of vapour smelling of lemon soap. Doris washed and Jacques dried. Jim watched them intermittently, and always asked himself how Doris could keep her old hands in such hot wa

ter. Sometimes she herself misjudged her resistance and left one hand immersed for a bit too long, snatching it out with a quick yank, shaking it, and saying, “Goddam, that burns.” When they had finished the plates and utensils, they put the other kettle to heat to make water for the glasses, which they left to soak until morning. They emptied the ashtrays and lined up all the empty bottles at the end of the counter. Afterwards, Jacques Plante cleaned the old plastic tablecloth with Windex and a rag. Half asleep, Jim sometimes heard Jacques Plante asking Doris if they’d forgotten something, but by the time Doris did the rounds and came to murmur words in Jim’s ear about times to come and things that would get better, he was beyond hearing anything.

Jim slept. They had gone when he woke up in the middle of the night to lay a log on top of the embers in the stove, and he was sleeping when his father woke at sunrise, pulled on his jacket, and left the cabin in silence to see the day dawn rich in mist and dew.

In the Midst of the Spiders

He travelled for weeks at a time, but it was always, whatever the city, the same airport, the same empty space, with its distant hubbub and jet-lagged travellers. He’d been killing time for twenty minutes, sipping a gin and tonic in the company of a red-faced fifty-year-old who was on the same flight. The man had told him his name, but he’d forgotten it. It wasn’t like him to forget names. That was his job, handshakes and slaps on the back, significant winks. He could—he ought to—remember the name of any random mortal stumbled upon in an airport or a trade fair. When he happened to remember the first names of their wives and children, that was even better. He’d had a professor of public administration once who liked to say that memory was a muscle you could train. The professor knew by heart almost every country in the world and their capitals. That had impressed him. Now he’d memorized the names of several hundred clients, their birthdays, their addresses, and always two or three personal details. He remembered who was the record collector and who the fly fisherman, knew who was happily married or getting divorced, who had a pregnant daughter or a son in detox. He also remembered what everyone drank. People always feel close to someone who can order their liquor for them.

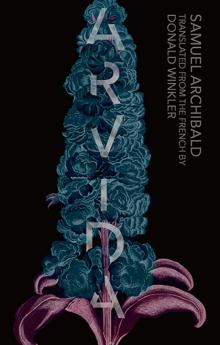

Arvida

Arvida